How it Came About

OUR WEBSITE BEGINNINGS

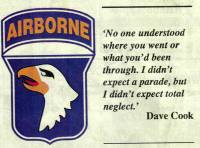

101st Airborne, 327th Infantry Regiment Vietnam Veterans Web Site

Reunions for “COBRA” Company started in 1983, but the article below was taken from the “Fauquier Life” newspaper, July 26, 1995, when they did a story called “A Time For Healing”.

A Time For Healing Bristersburg Home Is Site For Vietnam Veterans To Reunite And Mend Wounds By SANDY HUME, Times-Democrat Writer

They came last week to Bristersburg from far-flung places like Wyoming, Maine, Florida, South Dakota and Colorado, much like they had converged on Vietnam from different corners of the United States more than three decades ago.

Then a group of gung-ho kids, some only 17 and 18 years old and all of them volunteers, they were given the singular directive to wage war.

Their mission, at a 30th reunion of the 327th Regiment July 15, was one of healing. Their weapons were smiles, laughs, handshakes, hugs, tears – each one providing an incremental advance in the life-long quest to make sense of, and peace with, their common battlefield experience.

Their story goes back to the earliest stages of the Vietnam War. They were, in a sense the chips with which President Johnson upped America’s ante; the 327th Infantry, from the Army’s 101st Airborne Division’s First Brigade was part of the massive infusion of troops, which landed in the summer of 1965.

Almost from the moment they stepped ashore, soldiers in the 327th began to fight. Rapidly deployed and nomadic in nature, they stayed in the field straight through Thanksgiving.

“No other unit covered as much ground as we did, or spent more days in the field,” recalled Dave Cook, a 53-year old history teacher from Maine who had been a mortar-man in the 327th’s “C” Company. “We set the standard for field efficiency.”

They fought into 1966 through some returned early with injuries. And some never returned at all.

The names came up as the stories came out, 30-plus veterans of the 327th telling and retelling their tales seated at picnic tables outside the home of county resident Ken Ihle. There were tents and coolers filled with beer – frequently visited on this hottest day of 1995.

The air, thick with humidity, was also charged with emotion. A listener is uncertain whether a story will end with guffaws or quiet sobs.

“I remember betting Fred Johnson twenty bucks on the seventh game of the (1965) World Series,” remembered Jack Lockner, a platoon leader from Minnesota whose money was on the Twins. “Drysdale beat them and Johnson called us in off patrol. He said, “Give me the $20 now. You might not make it back and I don’t want to get tied up in any estate dealings.”

A handful of vets roared with laughter.

Some names seemed to come up over and over in the reminiscences, like Sgt. Davidson. A platoon leader uniformly described as one of the most popular and respected men in the 327th. Davidson was killed in action on March 9, 1966.

“He was probably the finest human being I’d ever known,” said Robert Morton, a 53-year old school superintendent from Henin, Ala., with a shake of his head.

“Everybody kind of leaned on Sgt. Dave. It was a real shock to everyone when he was killed,” recalled Cook.

What was remembered only with a little prodding were not the stories of field maneuvers nor the occasional light moments amid the heavy task of war, but the scarring struggles that began upon their return stateside.

It stands as one of the worst blemishes in American history, the self-righteous scorn and indifference heaped upon the wounded and confused soldiers returning from Vietnam. Their country had asked – and later ordered – them to serve. They answered the call, enduring often unspeakable agonies while retaining all the while their pride in their uniforms, their mission and their nation.

And when they made it home they encountered the further trauma of fellow Americans dismissing their service as ignoble and – particularly in the early phases – as trivial.

And when they made it home they encountered the further trauma of fellow Americans dismissing their service as ignoble and – particularly in the early phases – as trivial.

“I was treated mostly like I’d been on a Boy Scout camping trip,” said Cook. “No one understood where you went or what you’d been through. I didn’t expect a parade but I didn’t expect total neglect. We just felt so used and abused, like we were dropped off at the end of a brutal ride, like, OK, that’s it.”

Cook found the Army to be of little solace, and veterans’ groups to be of none at all. He did not join the American Legion, he said, and never will.

“I just felt that when we needed the support of them the most, they didn’t want us to join – or even made fun of us. I felt my military experience was valid, and to be put down by some guy who folded blankets during World War II in some place like South Carolina?

“I suppose,” he said, cracking a thin smile, “that’s one of the bitter things I let myself hold on to.

“In search of support, many tried to track down their buddies, which proved a more difficult task than they expected. Addresses were hard to find, as was cooperation from the military establishment.

But for the 327th, a “critical mass” of eight to 10 men persevered. They tapped whatever channels they could, relying on a military database here and word of mouth there. The result was the first reunion in 1983, and they have grown in size every year since.

“It’s a healing process, another layer of scar tissue over the wound,” said Cook. “It’s a big catharsis – we spent 20 years butting out heads against things trying to get through. I think there are some guys who don’t want to come, who don’t want to stir it up, but they’d be a whole lot better off if they did.

“When you leave here you feel like some load has been lifted, like you have some peace. All we left Vietnam with was our friendships. It’s bad enough losing the war, but you don’t want to lose that.

“If you want to get touchyfeely,” he said, “we are our own support group.”

Morton, the Alabama school superintendent, remembered being contacted for the first time three years ago.

“They called me on Christmas Eve,” he said softly, looking down at the ground. “I just went out on the back porch and cried and cried and cried. My wife came out and said, ‘What’s wrong?’ And I told her , ‘Honey, I just got the best gift a person could ever ask for.’ ”

Attending his first reunion, Morton admitted to having felt some ambivalence. “You have mixed emotions. You want to see them so bad but it’s kind of painful,” he said. By Saturday, though, the uncertainty had evaporated.

“It was worth every mile I drove,” said Morton, smiling.

First Sgt. John “Russ” McDonald, a 26-year veteran who served in the Korean and Vietnam wars, was one of the 327th’s company commanders, a man who molded warriors out of enthusiastic, but inexperienced young men. He knows how some have tried to de-legitimize their service – “I’ve never been in a war, just police actions and conflicts,” he said with a wry grin.

And he knows how war memories can force themselves to the surface unexpectedly, like when he walked out of “Forrest Gump” as the Vietnam scenes began.

“It was just something I didn’t want to see,” he said.

He will also tell you how much it means to him to see the grown men whom he still considers his kids.

“I felt better about it all when I left here last year,” McDonald said.

His wife, Faye, estimated that their phone bill runs as high as $300 per month due to Russ’ attempts to track down his kids – and from the conversations that ensue when he does.

“It still bothers him because he lost so many troops. But he’s not one who believes in flashbacks, because he believes that you have to make peace with what you’ve seen and what you’ve done,” said Faye, whose Job it was during the war to visit the wives of men who’d been killed. “It’s very important for him to be here. There’s a closeness and a camaraderie that you won’t see in many outfits.”

For some, helping vets come to grips with their Vietnam experiences is a part-time job. Cook writes a column for a paratroopers ‘ newsletter in which he attempts to reunite long-Iost soldiers. “I’ve been pretty happy that I’ve been able to hook people up,” he said. “I’ve had guys call me in tears. As I see it, it’s the least I can do.”

For others, it is a full-time job. Mike Bishop, who served in the 327th’s sister battalion, takes vets on tours of Vietnam, revisiting the actual scenes of battles in the hopes of putting perspective on the memories that haunt so many minds.

“The war’s been built up in our whole culture,” he said, “but you get there and it’s not this mythical thing. It’s just this country, and the people are so friendly and so much hasn’t changed. It kind of dissipates the whole thing. It’s a real catharsis.”

There are, of course, others who did not fight in the war but had their lives deeply affected by the outcome of its battles. Ken IhIe ‘ s reunion offered support for them, too – people like Charlie Davidson Jr., the son of the popular company commander whose death stunned the kids of the 327th.

Davidson had been only 14 at the time of his father’s death. He thought he knew his Dad well, he said, but he learned much more about him by the end of the weekend.

“This gives me some kind of closure to it all,” said Davidson. “And it feels very good to hear all these kinds of things said about him.”

In a brief but poignant memorial service during the reunion, Davidson stepped to the stage to say a few words to the men who had tracked him down and invited him to Bristersburg. With soldiers holding their hats in their hands, their wives listening intently, Davidson recalled how he made his way to the Vietnam Memorial in Washington, D.C., found his father’s name, and traced it onto a piece of paper.

“I thought at the time that for a man who had given his country so much, and loved his country so much, that he deserved more than this,” said Davidson, his voice strained.

“I know having met many of you and talked to you, and shared this weekend with you, that he did have much more,” he said. “Thank you.”