Vietnam

Run for the Wall Report 2003

Dear Friends:

On May 14, 2003, my friend, Judy, and I participated in the Run For The Wall (to the Viet Nam War Memorial in Washington, D.C.). This is an annual event to honor those vets who served in

Viet Nam and especially to remember those who never came home, as well as the vets from other wars. This was the fifteenth year of the Run. The Run was an event that I felt particularly feel compelled to do at this time in my life and at this time in our countries time in history. I had talked to so many people who participated in this event in years past, and who told me that it was the most incredible and rewarding trip that they’d ever taken. They were right!!!

Judy and I took my car and followed the motorcyclists through several states to our final destination—Vietnam War Memorial, the Wall. In preparation for the trip, I loaded up car tools, generators, a cooler, etc., (and too many clothes, including leathers, rain gear, helmets, and first aid supplies). Judy and I prayed that we would make it across country without incident, and we did.

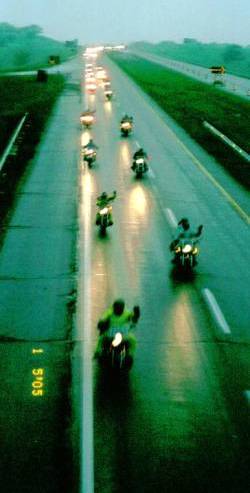

Judy and I took the Central Route, starting off in Ontario, California, along with about 300 motorcycles to start, and the group was gradually joined by several hundred more bikes as we crossed into various states toward our final destination in Washington, D.C.

I have to tell you that this event was one of the most incredible and life-changing events for me, Judy, and so many other of “our new brothers and sisters” that we had come to meet, love, and respect during the trip. We developed very close friendships throughout the trip, not only with people on the Run, but also with people in various states through which we traveled. We shared the highs and lows. We cried and we laughed. Once Judy and I cried and laughed at the same time, which was truly a sight to see!!!!

We visited Veteran’s Hospitals, a school, the Navajo Nation in Window Rock, New Mexico, veterans’ memorials, an incredible sanctuary and monument in Angel Fire, New Mexico, and with people in many cities across the country. We were fed wonderful meals by veterans groups, Harley Davidson dealerships, by people from entire cities who prepared huge home-cooked meals, and service groups. We had children come up to us to ask for our autographs because they believed that the  vets and those who were supporting this mission were their heroes!!! The looks on their faces, as we came to their school, was priceless—so much curiosity, adoration, excitement, and wonder.

vets and those who were supporting this mission were their heroes!!! The looks on their faces, as we came to their school, was priceless—so much curiosity, adoration, excitement, and wonder.

The weather for our first four days ranged from pleasant to very, very hot. In Salina, Kansas, at 5:30 a.m., we awoke to what sounded like an explosion, only to discover that we were in a torrential downpour. The Vets who were camping got soaked and from then on, until we got to Washington, D.C., we traveled in sometimes very heavy rain. Judy and I felt guilty to be in a car when so many others were riding their bikes in the rain and cold. I had been fortunate to be able to ride with a few different Vets on occasion, and Judy drove the car—thank you, Tom, Larry, and Steve for allowing me to ride with you part of the way.

Oh, I have to tell you about Wendy!!! He was an 80 year old W.W.II vet, who drove his trike, which pulled a small teardrop trailer, and who almost made it the entire route. Unfortunately, he

Images courtesy of Rex Rosenberg www.bugwing.com

had to turn back in Missouri because his buddy’s trike broke down. He was so interesting and so much fun. I regret not exchanging telephone numbers with him, so if anyone reading this knows Wendy and can provide me with a way to contact him, I will be very grateful!!!!

Judy and I, on two occasions, drove ahead of the group to take pictures as they rode down the freeway. We stood at overpasses, waived flags, and met some wonderful people on the bridges. Two ladies from Raton, New Mexico, were out waiving flags at 5:30 a.m., way before we got there, and they were having such a great time sharing their patriotism and enthusiasm with all the passing motorists.

In Salina, Kansas, a police officer stopped to see if we needed assistance, and when we told him that we were waiting to greet the group from the Run, he turned on his police beacons, and saluted the group, and Judy and I waved flags and took pictures (in the rain, I might add!!). What an incredible feeling to honor these wonderful vets and pay homage to the Vets on the Wall.

So many other things to write about, but the most important and most moving event for me was being at the Vietnam War Memorial—the Wall. I cannot begin to express the many thoughts and feelings I had as I examined the names on the Wall and saw the tributes that so many people left there for their loved ones. I found the name of my friend from High School on the Wall, Pete Mills, and my tears really started to flow. It was one thing for me to have known that he gave his life for this country, but when I saw his name on the Wall, that reality actually set in for me. If was quite an interesting phenomena for me when I found myself actually having a “conversation” with him when I reached out and touched his name. People around us were crying, praying, standing silently, and honoring the fallen Vets, each in their own way. At that time, I found myself feeling proud to be an American, and proud to be standing in the company of my heroes—those Vets who gave the ultimate.

Our trip back to California deserves another newsletter, which I will save for later. All in all, we were gone for a total of 21 memorable, emotional, and incredible days.

I am going to end my message now, however, I wanted to share with you a most beautiful and moving article/journal that Judy wrote and shared with me about her feelings and experiences during the Run. Her journal is attached to this e-mail. When I read her article, I felt as though I was re-living our adventure. I was so very honored to have Judy accompany me. Everyone who met her, fell in love with her. She is compassionate, fun, interesting, caring, loving, and a true friend. She has a great sense of adventure, sense of humor, and sense of honor—in other words, she is a person of GREAT integrity. Judy and I are already talking about and planning for the Run For The Wall for 2004. Judy even talked to her son, David, about him building her a trike!!!! She will definitely have to have her camera mounted on the trike so that she can ride and take pictures at the same time!!! Judy took 26 rolls of film; I took 10 rolls. The pictures are incredible, but sadly we didn’t take enough. Perhaps next year!? Signing off for now, Love, Valerie

MEMORIAL DAY WILL NEVER BE THE SAME

Memorial Day has changed forever for me – because of a group of bikers.

When a longtime friend invited me to join her on a motorcycle ride called “Run For The Wall,” I said why in the world would a 65-year-old woman want to travel with a bunch of motorcyclists across the country? Valerie told me these were not just “a bunch of motorcyclists”; they were Vietnam vets and vets of other wars and their supporters who do this because they don’t want our country to forget about the POWs and MIAs who have never been returned home. They also do it for the many Vietnam Vets who did return, but to an America hostile to those who fought over there. Anti-war sentiment was strong, and many returning veterans were not welcomed home as heroes, as veterans of previous wars were. Many vets refused to talk about their time in Vietnam; some even denied they were over there in order to avoid the questions and accusations.

The Run For The Wall was started in 1988 by two Vietnam vets who believed America needed to be reminded of the POWs and MIAs: nearly 2,000 unaccounted for in Southeast Asia, some 8,000 still in Korea, and 78,000 still unaccounted for from World War II. The message has been carried every year since, ending at the Vietnam Wall in Washington D.C. to honor those who gave their lives in service of their country, not just in Vietnam, but in all wars. On Memorial Day, they join hundreds of thousands of other motorcycles in Washington, D.C. in “Rolling Thunder,” a parade of motorcycles honoring our veterans.

This was the 15th year of the Run For The Wall, and on May 14, after a prayer for safety, a color guard honoring the vets, and a rousing send-off by local citizenry, we left with almost 300 motorcycles from Ontario. More motorcycles would join the group along the way across the country. Our group took the central route, but there was also a second group of about 80 bikes that took the southern route, and another group that was taking a northern route for the first time. The three groups merged in West Virginia, and National Park Police escorted us into Washington, D.C. By then we had about 600 bikes.

By the second day, riding with hundreds of vets on motorcycles had lost its strangeness. When I had committed to the ride, I wanted to feel a part of the group, so before we left I pulled out a denim vest, sewed a large “Run For The Wall” patch on the back, and added various pins given to me by my new friends (with rather strange names, like Fingers, Rock, Jungle Jim, Trouble, Little Big Mike.) Some of us were also sporting bright pink buttons with the letters “FNG,” to identify us as a first-year participant in the Run. I learned that in Vietnam, no one wanted to be stuck with the “f—— new guy” because he was green and bad luck and could get you killed. On the Run, there is no such stigma in being the FNG; in fact, the new guys (and gals) are welcomed heartily and given support on their first trip to the Wall. It’s become a custom to take a pin off and give it to an FNG for his vest. Maybe they’re trying to make up for having treated the FNGs so shabbily 30 years ago.

The Run was a lesson in organization. Just as they had in the military, the riders followed the rules strictly, because to not do so was to risk injury. Leading the group was the “Missing Man Formation,” with different riders being given the honor of participating. Following them was “Doorgunner,” the central route coordinator. After him were the dozen or so Road Guards, wearing bright yellow arm bands. They rode up and down the formation, keeping the group in order and safe in traffic, positioning themselves at busy intersections and freeway on- and off-ramps in order to guide the group on and off safely. Police and CHP often escorted us through heavy traffic, sometimes stopping freeway traffic to allow us to pass without splitting up. Sometimes off-duty Highway Patrol officers escorted us to the next state border, where that state’s officers would take over. A number of active and retired law enforcement persons go on the Run, and others volunteer to escort the riders on various segments of the ride.

After the Road Guards came the motorcycles, followed by trikes, followed by motorcycles with sidecars, followed by trikes and motorcycles pulling trailers, followed by the “Last Man Vehicle.” The driver of the Last Man Vehicle, Skeater, was entrusted with keeping an eye out for bikes with problems. If a rider pulled away from the group, a simple wave from him, or a thumbs up, meant he was OK, probably just stopping to take a break. But if he raised both arms overhead, and waved them back and forth, it meant he was having trouble with his bike, and Skeater, seeing the signal, would radio to one of the support vehicles behind him, who would watch for the rider and stop to help. If the bike was disabled, it would be loaded onto the trailer and taken to the nearest repair shop. When it was repaired, the rider would catch up with the group later.

After the Last-Man Vehicle came the crash vehicles – carrying medics and emergency first-aid supplies. One of the rules of the Run was to never stop for downed bikes; it would only cause chaos with traffic. The crash vehicles would stop and handle any emergencies. Following the crash vehicles were several trucks pulling trailers to pick up disabled bikes. Bringing up the rear were the four-wheelers.

Motorcycles rode two-by-two, and followed the road guards’ every order. When we came to a narrow road, Doorgunner would hold up one finger, and the riders would pass the signal down through the ranks. Everyone knew this meant the riders on the right must drop back a half position, so that the two lines were staggered, instead of side-by-side. This way they could close up ranks and form a narrower line. When the road was back to normal, Doorgunner would hold up 2 fingers, the signal to get back into normal formation.

But nothing compared to the organization required to gas up 300 bikes. The gas stations are chosen ahead of the ride, and the station owners know exactly when to expect the group. Several pumps are reserved for the group, and the riders line up two-by-two on each side of a pump, passing the nozzle back and forth. Riders are required to round up their payments; if their gas came to $4.20, they would pay $5. This is not just to save time, but to have extra to pay to gas up the support vehicles. The group has gotten so good at the procedure that they once gassed up 250 bikes in 14 minutes.

Every morning began with breakfast, a riders’ meeting, and a prayer by “RC,” the chaplain. At the meetings Doorgunner briefed us on the upcoming day’s schedule and also on any accidents. There were at least a dozen bikes that went down for various reasons; one vet broke her ankle in an accident, but continued to the Wall in a car, in a cast and on crutches.

It was an exciting trip, but also a somber one. This wasn’t a vacation – it was a mission. Many of the vets were going to the Wall for the first time, and it was deeply emotional for them. For those who had been suppressing memories for over 30 years, releasing them was painful. The Run helps them deal with those memories, and allows them to experience the welcome home they never got. No one is alone on this ride; they all support each other. It’s commonplace to see both men and women crying as they face their demons on the Run, not only at the Wall, but all along the way. So many things bring back memories: seeing a replica of the bamboo cages POWs were kept in, or hearing the roar of a Huey hovering overhead to greet us at one of the stops. In Hugo, Colorado, I met “Bill,” from Oklahoma, who tried but couldn’t hold back the tears as he told me he just had to do this in order to have closure. He joined the group in Oklahoma last year, but turned back the second day; he just couldn’t do it. This year he rode his bike out to California so he could go “all the way.” But he didn’t know if he could make it. I hugged him and told him yes, he WILL make it, that he was surrounded by people who cared about him and would help him. I talked to him again on Day 6 in Kansas, and he seemed to be holding up. When I next saw him in West Virginia; he was sobbing in the arms of another vet. I didn’t see him after that — I hope he made it all the way. Maybe I’ll see him again next year.

America is definitely trying to make amends to Vietnam vets. cities, organizations, businesses, and individuals donated to provide every meal and some of the gas for the group all the way across the country. We had breakfasts, lunches, and dinners in campgrounds, parking lots, VFW Halls, and city parks. We visited with veterans in VA hospitals, visited war memorials, and laid a wreath on the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier. We were escorted from city to city or state to state by various state and city police and highway patrols. We were greeted by police cars, fire trucks, and a Huey helicopter. We were honored by the Navajo Nation in New Mexico, where we met the original Navajo Code Talker, subject of the movie, “Wind Talker.” And we were welcomed by Victor Westphal, who almost single-handedly built “Angel Fire,” a beautiful, soaring, white angel wing memorial, in memory of his son David, who was killed in Vietnam. This is a true sanctuary, revered by veterans, and one of the most special stops on the Run.

When we arrived at one of the VA hospitals, a rider told me they had met a 101-year-old veteran there last year, and the group had given him a motorcycle vest — he hoped the gentleman was still there this year. He was – smiling and wearing his vest.

I was truly amazed at the reception the vets received all across America. Whole towns came out to wave flags as we passed through. People – sometimes two, sometimes dozens – stood on freeway overpasses, waving both American flags and POW/MIA flags, and held signs saying “Welcome Home!” and “Thank you for our freedom.” I had never before taken much notice of the POW flag, but now I’m painfully aware of what the stark black and white flag stands for. Sometimes other vets stood along roads or on overpasses and saluted while the hundreds of bikes passed. The vets returned the salutes with an upraised arm and clenched fist.

Riding with the group was an intense and moving experience. The vets call themselves brothers and sisters – and they mean it. At one of our afternoon stops, we were told that one of the riders had just gotten a phone call — her nine-year-old son had been hit by a car and was in the hospital. They passed a hat to collect money for her to fly home to her son. I’m sure there was more than enough for her fare; I saw $50 and $100 bills in the hat. They hug each other freely, and shed tears freely.

I’ve been changed by this experience; I’ll never again take the men and women who fight for our freedoms for granted. I’ll do whatever I can to remind our government that our POWs and MIAs must be accounted for. And maybe I’ll do this every year now; like many others before me, I don’t think I can stay away.

Jungle Jim Grainger

Jungle Jim Grainger